One very distinct and time-honored tradition in Japan is the “senpai” and “kohai” relationship between classmates and work colleagues.

A senpai is usually an elder or senior person who has a higher level of experience than the younger or junior person (kohai). This hierarchical relationship can be related to personal experience, job position, education level, or simply age within a particular organization, institution, or company. Often times, it merely means the one person happened to join the club or team before the other person … even if the younger person might have more ability than the older person, it is likely that the person would be referred to as kohai.

The role of the senpai is to act as the “go-to” person for the junior person to offer assistance, counsel, or even friendship to the “newbie” or kohai. In return, the kohai should afford the senpai a higher level of deference, respect, gratitude, and even personal loyalty. This system is most commonly seen in the context of schools, especially in school culture clubs and sports teams (bukatsudo).

The terms are gender neutral in that they may refer to both males and females equally.

Due to the proliferation in the West of Japanese manga and anime, the term is not completely foreign to people who are aficionados of Japanese comic book culture. Early on when Japanese anime was gaining in popularity overseas, the term senpai was sometimes misunderstood to have a sexual context, but it simply is an honorific title of respect that refers to the relationship of an older classmate or colleague who is wiser or more experienced in things than the younger, junior person.

The senior/junior relationship has its roots in Confucianism, but has become a very distinctive and unique aspect of Japanese culture and tradition, even though the original concept was imported.

Using senpai to refer to an older classmate is still very common and is used frequently amongst younger people. I often hear my students in class address a friend or classmate with senpai in normal conversation. Most often, the two students belong to the same university club or play on a sports team together.

It has been my experience to notice the senpai/kohai relationship and distinction occurring at about the time children enter junior high school. I don’t notice it so much among younger children, but once they get to the lower secondary education stage of their lives, it starts to be used. This perhaps could be because this is the time when they begin to play sports more earnestly and start to join student clubs.

The tradition then continues through university and into their professional lives after joining the work force. Especially if a new worker joins a company where there are people from his/her university already employed there, the term would be used when referring to an older colleague who is already established in the company or school (in the case of teachers).

This is not to suggest that those who are senpai have it made in the shade in being given deference and respect by their underlings or kohai. Being a senpai is a huge responsibility and has real implications for the senpai; in order to be a good elder to his/her kohai, the senpai must be good at advising their kohai by offering support and assistance when needed to the junior person. If a senpai is too bossy, selfish, overbearing, and/or treating the kohai badly, then the senpai will lose the respect of the kohai which is avoided at all costs.

A bad senpai is the kiss of death in the social-hierarchy of the group because once one gets that reputation, it is hard to regain that respect once again. The relationship runs so deeply within Japanese culture that people maintain lifelong senpai/kohai relationships long after the initial association for the hierarchical relationship has finished.

The other side of this hierarchical coin is that the kohai must show his/her senpai proper respect and deference in order not to be labeled as a contrarian or a disrespectful antagonist. If a kohai insists upon not showing the needed respect to his/her senior, then the kohai will likely be put in his/her place (if not by the actual senpai then by other kohai or senpai in the group).

A tired an overused saying in Japan is “the nail that sticks out gets hammered down” but it is quite apropos in this situation. The kohai will quickly be admonished by the others in the group and likely be told to shape up or ship out.

The senpai/kohai system in Japan is, in part, the oil that keeps the finely-tuned cultural and societal inner workings running smoothly. People know their place and behave accordingly. There is a related concept that is quite prevalent in Japan that is marginally related to the senpai/kohai tradition and that is “amae.”

Amae is a Japanese character trait that emphasizes the need to be dependent upon or attached to others in order to remain in good favor with the group. A worker may ask a boss a softball question at a meeting to show his/her dependence upon the higher up. Even if he/she knows the answer to the question, it is considered appropriate to show dependency upon the experience or wisdom of the other person in the supervisorial role.

On first reflection, one would think that something like amae wouldn’t be a positive character trait, especially when looking at it through an American cultural lens where independence is expected, welcomed, and admired. But in Japan, a sense of dependency upon another person, group, or work situation portrays the importance of the group and one’s desire and need to have that group or person to depend upon.

The ultimate goal I think is for the person to display the need for maintaining a harmonious atmosphere within the shared space which may or may not be related directly to individual specialties or social boundaries. The bottom line is it shows a need for mutually beneficial relationships with those with whom one is interacting with frequently or on a regular basis.

Amae is such an ingrained aspect of Japanese interactions that I believe it is largely done unconsciously in depending upon others to do things for them. My first introduction to the concept of amae was when I read the book “The Anatomy of Dependence” by Takeo Doi in the 1970s. His description of amae was so interesting to me back then, and over the past nearly 40 years I have had so many opportunities to see it play out around me in my interactions with Japanese people while living and working in Japan.

If my memory is correct, one aspect Doi focused on in the book was how this sense of dependence is similar to how children will purposefully behave childishly in order to get parents to indulge them more and he believed that this need extends into adulthood and generally Japanese people yearn for this child-parent type of connection with those whom they must interact with in daily life.

All this talk of dependence and amae makes me want to pull Doi’s book off the bookshelf again and reread it!

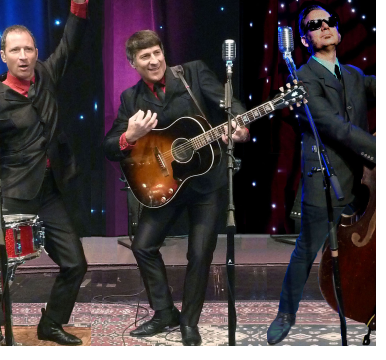

Photo: A kohai (left) is visiting a football stadium in La Crosse, Wisconsin, with his senpai (right). They both belong to their own university's football club. The senpai is also a coach for the football team.

Get the most recent Shelby County Post headlines delivered to your email. Go to shelbycountypost.com and click on the free daily email signup link at the top of the page.

.jpg)